By G. James Daichendt

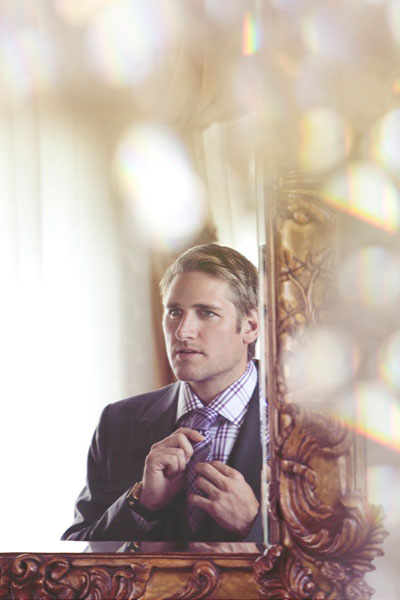

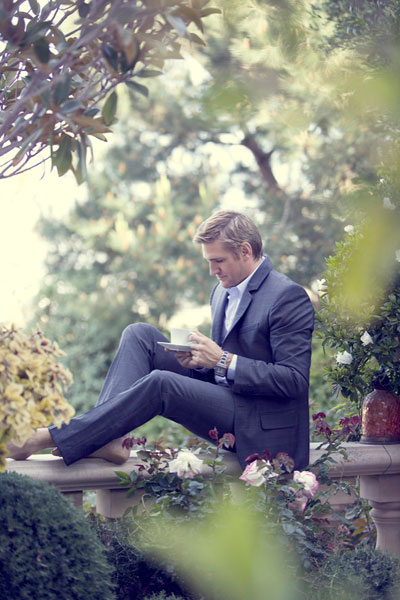

Photography by Michael Stonis

Assisted by Rod Foster and Connor Stewart

Grooming by Helen Robertson/Celestine for SAMPAR Paris

Styling by Toni Ferrara | Assisted by Nicole Velasquez

Bloodied and bruised, he climbed the stairs back to the kitchen so he would not fall behind as the orders stacked up. The gritty reality of the fast-paced restaurant industry that saw Curtis Stone falling down a flight of stairs while rushing between shifts directly coincides with Stone’s fierce competiveness. His humble start, quick progression, and eventual stardom are apt for a sports metaphor. Like the ball player who made it to the pros, Curtis has paid his dues and is now playing on a different level.

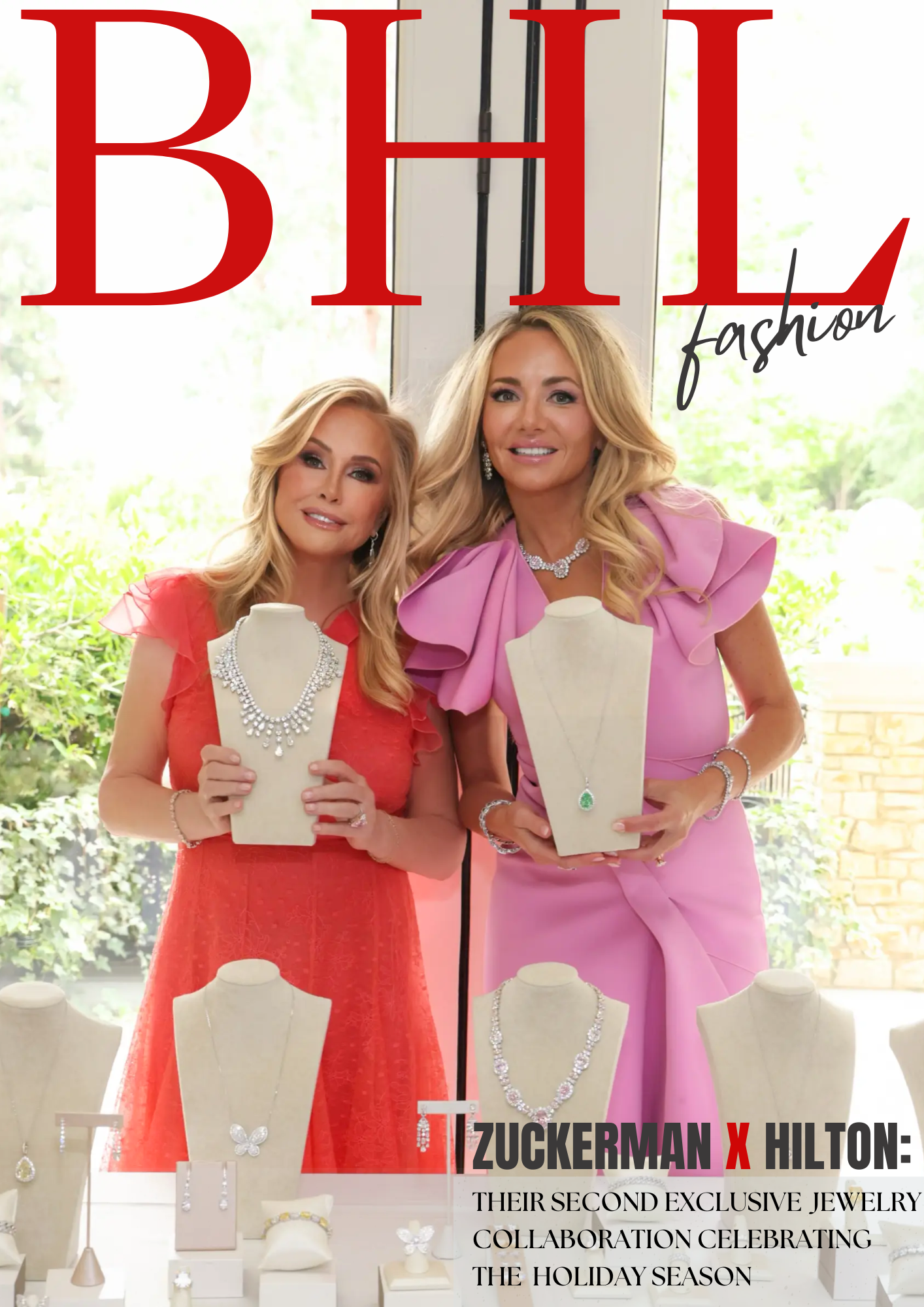

We catch up with Curtis poolside at an enormous Beverly Hills mansion for our photo shoot—perhaps are presentation of his life these days. While the camera crew sets up for the upcoming water shot, Curtis opens up about his motivations, cooking culture, and the advent of the celebrity chef.

The boom in restaurant sales and the corresponding foodie craze has turned America upside-down in recent years. Gourmet food trucks, an explosion of cookbook publications, and a long list of celebrity chefs instructing, competing, and vying for the attention of viewers have transformed television and the way Americans experience food.

And Chef Curtis Stone is right in the middle of this cultural revolution. A regular on television programs like The Biggest Loser, star of the breakout hit Take Home Chef, and an investor and judge on America’s Next Great Restaurant, he is now hosting season three of Bravo’s Top Chef Masters. With a dizzying schedule that resembles a concert tour, the chef carries some guilt for the image he embodies. Being a chef after all is a difficult job and one that requires years of training and hard work, something the camera and photo shoots tend to gloss over and present in a neatly framed package.

Unfortunately, the cult of celebrity has garnered unrealistic expectations—a situation viewers enjoy as many cooking shows feature Survivor type competitions with someone eliminated each episode. To be a great chef requires a commitment to food. When asked how he learned to cut onions, he references thousands of hours on the cutting board. This is not something one picks up with a simple technique but only through hard work–something Curtis learned at an early age.

Unfortunately, the cult of celebrity has garnered unrealistic expectations—a situation viewers enjoy as many cooking shows feature Survivor type competitions with someone eliminated each episode. To be a great chef requires a commitment to food. When asked how he learned to cut onions, he references thousands of hours on the cutting board. This is not something one picks up with a simple technique but only through hard work–something Curtis learned at an early age.

Curtis remembers these times well, and the painful and grueling aspects are not tough to drag out of him. In what Curtis describes as a “pivotal decision,” the young Aussie desperately volunteered to work for free in order to cook with the highly regarded Marco Pierre White in London. White is a perfectionist with impeccable standards and Curtis long admired the revered chef. The decision paid off, as he began right away at The Grill Room at Café Royal. With a sly grin, Curtisdescribes the atmosphere as “a place where if you didn’t get fired that day then you did a good job.”

The progression of Curtis’ chef career over eight years under White saw a number of highlights: a rise in responsibilities, a Michelin star, and eventually the position of head chef at Marco’s critically acclaimed flagship restaurant, Quo Vadis. He even played a significant part in building a cookbook for White. The trials of collecting awards and competing for recognition within a world that is full of long hours, weekends, and injury is demanding and stressful. Miles from the television studio, a typical day is much more akin to physical labor as one strives for perfection in the kitchen.

These beginnings were steeped in learning and mastering the art of fine cuisine, a craft that’s been lost in today’s fast paced culture according to Curtis: “Fifteen years ago food was at its fanciest…nowadays it’s farm to table and you splash it on a plate.” This insight is why we want to watch Curtis cook and provide feedback to aspiring chefs.

At any time of the day, one can watch a cooking demonstration on television. Often these programs opt for the quick and easy solution that can be reproduced at home in a relatively short format. This paradigm is a symptom of the modern family that view the long hours of food preparation as a pragmatic expenditure in exchange for ready-made meals. The realistic expectations can be recreated while the longer gourmet demonstrations are an extension and an invitation to dine out.

These cultural shifts did not happen overnight. Curtis believes there have been some significant changes in the United States that elevated cooking shows into the wildly popular paradigm that they have become. Over the past few generations the make-up of the family has changed. Households are busier and less traditional.As a result of these changes, there are less folks committed to the art of cooking. Households run by a single parent or two working parents who find it difficult to balance the time needed to prepare a traditional meal.

The television programs featuring chefs or the process of cooking fill this void. It is an olive branch for the traditions lost, and the popularity certainly speaks to our cultural condition as hungry Americans. We desire it for entertainment and for the lost experiences of eating together. It’s a connection to the ritual of preparing and enjoying food as a community. Even if it’s just you and the TV.

The process of enjoying food is offered symbolically as the viewer watches everything from the initial conceptualizing, the selection of the proper ingredients, the exciting and mouth-watering cooking, and the eventual enjoyment of the food. In fact, the host actually samples the food and attempts to express and explain how it tastes. The virtual experience is far from perfect,much like a super model choosing to do talk radio. But the visuals do get the taste buds flowing. These aspects are made physical when a cookbook (of which Curtis has several) is bought and the experience is replicated at home. It’s a tempting experience that Curtis recently engaged as he sought to bake hot cross buns. Overwhelmed by the visuals from his research, he became so hungry that he rushed out for tacos down the street.

Over the last decade, restaurant sales have increased over 50 percent and the subscriptions to the Food Network have jumped through the roof. A history that started with Julia Child and her television program The French Chef and continued through to Emeril Lagasse now moves onto a younger generation represented by Curtis Stone. It’s a phenomenon that shows no sign of slowing down.

Yet not all chefs are created equal, and Curtis divides these folks into bakers and cooks. Good bakers “like to follow instructions and follow them very carefully.” They are organized and need structure in order to achieve their desired outcomes. You might hear a baker say something like: “You can’t just throw some raisins into a mix because you love them; it changes the way the dough rises and ultimately ruins the recipe.”

In contrast, good cooks are able to be much more creative in the kitchen, and in the case of Curtis, he prefers to let the seasons influence the way he cooks. Preferring to use ingredients that are fresh and available, he changes the ingredients based upon what is fresh and available. He sees no reason to start with ingredients that are subpar. This is a characteristic that a good baker does not have the luxury of doing. Curtis humorously acknowledges that the disadvantage of a creative cook is “messy bedrooms and bloody disorganized lives.”

Clearly, cooking food is a performance for Curtis, a ritual that begins the moment the decision to cook takes place. From the time one enters a home, the smells overcome the entry way and the chef plays a central part in this experience. There is a kinship and empathy that the viewer feels with Curtis Stone in the kitchen and on the small screen. The connection comes through whether it’s a competitive context or when he is modeling proper eating habits. This is an important and much needed process, an experience that begins when the television is turned on and complete when we finally eat something.